Thanks for letting me think through all the wisdom I’ve gotten to take in over this summer so far. I hope that by the end of the summer, you and I will be able to find the arc in the content, and in the meantime, I hope you find the content interesting even if not every post is directly related to your own justice work.

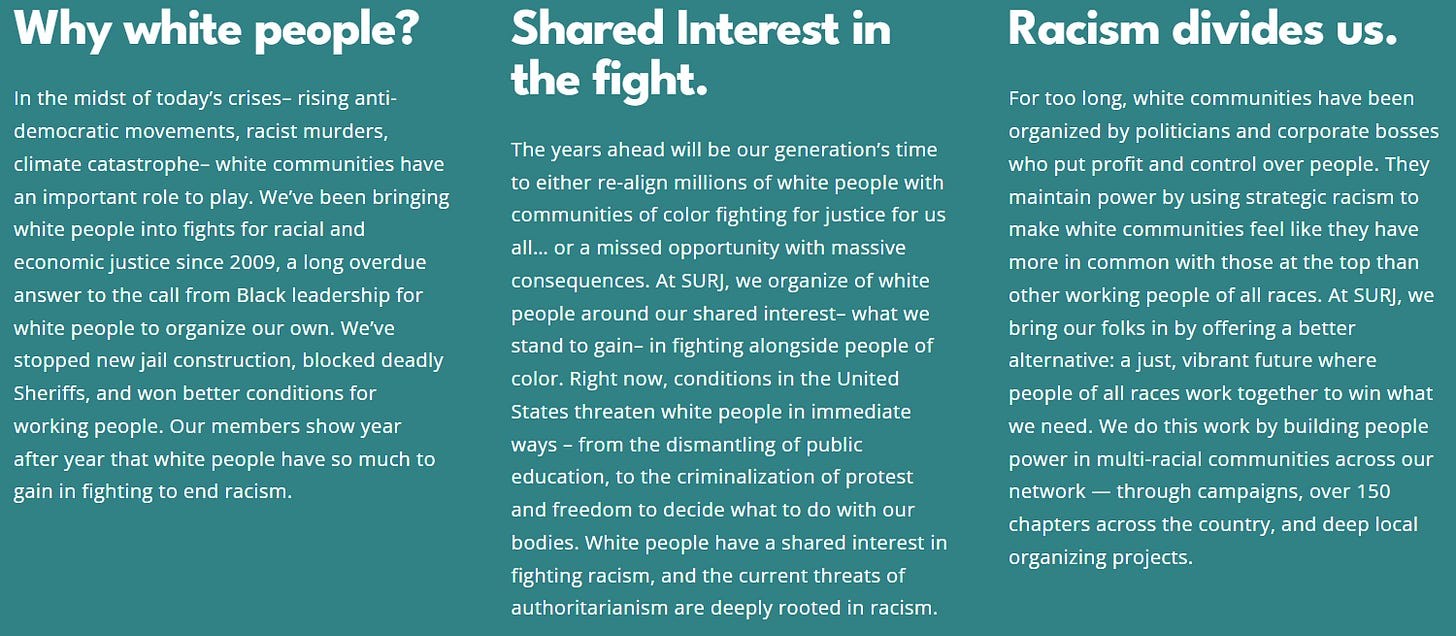

I’m still thinking about a workshop I attended at the 22nd Century Initiative’s anti-authoritarian conference in June. It was led by staff from SURJ, Showing Up for Racial Justice. I’ve followed SURJ over the years. Many friends have been active in it. While experiences vary from local chapter to local chapter, I’ve seen them do a lot of good. More interestingly, though, I’ve watched them evolve and shift in response to what they’ve been learning in the field. So I was excited to attend their workshop called “Dismantling Divide and Conquer: Gatting ‘shared stake’ organizing to scale.”

I came mostly for the “experiments and successes” they promised to share, and that’s definitely what stuck with me the most. But the whole framework resonated with my own learnings as an organizer. And while SURJ primarily organizes among white people, I found it helpful to have greater context for ways people of color organizers might collaborate with and even learn from SURJ’s experiments in the field.

In this newsletter I’ll look at:

SURJ’s background context

different models of white and multiracial organizing

An illustration of the model in action

How this connects to my, and possibly your, reflections on organizing strategy

A little history related to SURJ

The presenters talked about the ways in which their model was informed by the Black Panther Party and how they had trained the Young Patriots as part of a powerful “Rainbow Coalition” in Chicago as well as the teachings of Anne Braden, a white anti-racism organizer who was contemporaries with Rosa Parks. (For a really inspiring and important read about poor white people’s solidarity with Black Power organizing in the 1960s, check out the book Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Interracial Solidarity in 1960s-1970s New Left Organizing, which—pro-tip—I was able to read on Libby.)

I am not 100% certain this is the quote they used in the presentation, but Anne Braden did say, according to the Carl Braden Memorial Center’s facebook page,

“I don’t think guilt is a productive emotion. I really don’t know anybody who got active because of guilt. Everybody white that I know who got involved in the struggle got into it because they glimpsed a different world to live in … Human beings have always been able to envision something better. I don’t know where they get it but that’s what makes human beings divine I think.”

As someone who’s always thinking about effective organizing strategy and who had noticed SURJ’s evolution over the past decade or so (SURJ was founded in 2009 in response to the backlash against the USA’s first Black President), I was interested in what they shared about why they had evolved. They saw a great deal of growth in the wake of Michael Brown’s murder in 2014. According to the national organizing director who co-presented, after a few years, they found themselves reaching the saturation point of white people who were joining the organization sheerly because it was already clear to them how racism continued to function and needed to be dismantled. In order to reach further and bring in more people, their strategy would need to shift.

The shared interest organizing strategy

The director of faith organizing for SURJ gave a really helpful layout of three different types of organizing/training in white and multi-racial spaces as they saw it:

Race-avoidant

Privilege

Allyship

Shared Interest

The presentation broke down their distinct worldviews, organizing strategies and goals expansively, but let me share just a glimpse of what I heard. Race-avoidant organizing such as the model promoted by Saul Alinsky in the 1940s and beyond believes that discussing race alienates poor white people and that organizing based on shared needs is sufficient to create justice for all. The organizer noted that in this model, race ends up lurking in the background. If you’ve ever heard me talk about Saul Alinsky as Cautionary Tale, you know I agree with this assessment. In fact, sometimes this model has sometimes contributed to racist organizing even while moving forward important issues like sanitation and housing.

The privilege model is one you may have encountered in your workplace if you’ve ever been through cultural sensitivity training or something else akin to it. Its focus is individual and educational. There’s nothing wrong with that. We are trained into unconscious biases that affect our individual choices in the workplace and everywhere else. This model, however, implies that addressing individual bias is sufficient to eliminating racism, which is unfortunately not the case. (I’m not going into why here, but if you haven’t thought about that idea and want to talk, please do drop me a line.)

Allyship is the model I think many of us have celebrated and sought to practice as a huge step forward in our work to dismantle racism. It does recognize racism as a systemic issue rather than an issue of individuals’ biases. It generally focuses on the role of white people as supporting people of color-led organizing efforts and functioning primarily if not exclusively in a supporting role, as those organizers see fit. This is by-and-large the organizing model SURJ used for most of the years I was tracking them; I only noticed the shift to a different model in 2020, although I suspect the groundwork was laid much earlier.

Shared interest (or shared stakes) organizing as they described it is “Organizing white people into a multiracial victory.” The formula, as I heard it, was this:

Make clear that the current system is killing us so we’re going to unite to take on that system.

Start with the story of the person you’re talking to—find connections between it and the ways you’re going to fight alongside many others to address their needs.

Talk about what they will win—make it concrete.

Erin Heaney, the executive director of SURJ, wrote a very accessible piece on this organizing model in the Forge; just be prepared for a little ache in your heart as you read this piece from early 2024 and their hopes for how this model could affect the election outcomes. (I found it helpful to bear in mind how many decades go into successful culture shift work.)

The sentence the SURJ staff started the workshop with (which could have been an Anne Braden quote?) was this: “White privilege is real—but it’s not an organizing strategy.”

What I want to emphasize here is how delicate a dance this is. The folks moving this agenda are mostly white people who want to dismantle racism. They want to dismantle it because of the very real and diverse ways that people of color suffer under its weight. They want to dismantle it because it misshapes all of us. They want to dismantle it because ultimately it doesn’t serve the people it purports to help—white people. And yet, if they’re not careful, this model could easily tip into the limitations of race-avoidant organizing, where because race is ignored, no amount of housing and economic justice work will alleviate the gaps between white people and Black people in particular and people of color more broadly. Their organizing model has to cover the three points above, and it also has to be explicit about why this work has to come in partnership with people of color severely impacted by the same issues that affect them, and how people of color’s experience and wisdom is critical to the success of the campaign (and the movement).

This is a dance I have seen the Poor People’s Campaign embody incredibly well at the actions I’ve attended with them, both statewide and national. But while the payoffs are immense, it’s not an easy one to sustain. Which is why I was grateful for the case study the national organizing director, Kristina Lear, shared. This part is from memory, so I suspect I will get details wrong. Please forgive me.

An example of shared interest organizing in action

Kristina was active in the LA chapter of SURJ when a coalition they belonged to which had chosen to take on the issue of mass deportation. The strategy, understandably, was to walk predominantly people of color-majority neighborhoods to talk with people and ask them to sign a petition to add a ballot initiative in the upcoming election to provide effective alternatives to mass detention and mass incarceration. SURJ had just begun their work around shared interest organizing, so they asked the other coalition members if they could, instead of canvassing POC neighborhoods, canvass white neighborhoods, with a commitment to collecting 10,000 signatures. (If I remember correctly, they needed about 300,000 signatures, which the forty or so coalition organizations were going to divvy up, with a shared outreach strategy.) The other organizations said, “are you sure?” because that seemed like a much harder get, but they signed off on it as an experiment.

SURJ volunteers canvassed white neighborhoods and started their conversations with “are there any ways you’ve personally been affected by mass incarceration?” People often said no, but the volunteers asked a clarifying question. “Some of the ways people are affected by mass incarceration is losing employees, having to take over childcare when a parent is sent to prison,” and more examples, whereupon the person would often say “Oh, yeah—I’m raising my grandkids; my daughter got hooked on meth and was sent to prison” or some other direct connection. This is when the volunteer would share some of the ways mass incarceration was affecting the community more widely, what the alternative could look like, and how that might help the person they were talking with.

They reached their signature goal with great success, and once the coalition got the issue on the ballot, they also hosted town halls in white neighborhoods so that more people could be part of the conversation. Conventional wisdom would have said they should have focused on people of color, but SURJ’s efforts helped pass the ballot initiative and also began the ongoing work of bringing more people into their multiracial coalition.

Connections to my, and maybe your, research

As you know, I’ve been a fan of deep canvassing for a while; it’s a model of canvassing a neighborhood that involves deeper conversations, that starts with listening and includes a certain amount of vulnerability, plus it’s “evidence based,” which is kinda cool, right? If you haven’t had a chance to read Anand Giridharadas’s book The Persuaders, it has a great chapter on this method that captures how much discipline it requires but what magic can emerge from it. (As an aside, I first learned about this model from an episode of This American Life in 2015 which highlighted the real effects of deep canvassing. What inspired the organization to use the method was an academic study that, after this episode aired, turned out to have been fabricated. They were devastated. And yet, their own efforts contributed to a later, meticulously tracked study that did in fact prove that the method works. What a wild ride for research and for those poor canvassers.) The SURJ model isn’t identical but it has overlapping elements that bring me a great deal of encouragement about the model’s prospects.

I also noticed some of SURJ’s strategy shifts about five years ago when I attended a workshop they offered featuring Ian Haney Lopez, one of the researchers who has built out the Race Class Narrative initiative. Lopez is a legal scholar with a focus on critical race theory. His popular books include Dog Whistle Politics and more recently Merge Left: Fusing Race and Class, Winning Elections and Saving America, which takes on the moderate myth that if we avoid talking about race we can build a bigger coalition. Lopez and Anat Shenker-Osorio (featured in a different chapter in The Persuaders) partnered with Heather McGee (The Sum of Us) to explore how to incorporate race into political messaging while appealing to people of all races. Turns out there’s a formula (one that I got trained in by a communications staffer who works with PICO, a Saul Alinsky-based network of community organizing bodies, but one that has worked intensely on exactly this kind of organizing). The rigorously tested formula breaks down to this:

People [of these various classes and races] all want [this policy we know will serve regular people, which is why we’re campaigning for it].

[This group of people, usually corporations] have tried to distract us from that goal so they can [retain power or money, usually both].

But when we come together for [that policy issue], we can take on [those people] and win the victory that will give us [the vision of the world that is possible when this policy is implemented].

That’s from memory, and there are better explanations, but if you want the CUTEST illustration of this script, it’s this one created by political consultant Anat Shenker-Osorio. (She is the gold standard for leftist political campaigning, so it’s funny that the final pitch in this ad is just to vote for a particular political party, but it’s still a great ad.) You can read more about their quantitative research findings HERE, but reading that chapter in The Persuaders is a really great crash course, as is the book Merge Left.

I also wanted to write about connections between this work and that of the Institute on Othering and Belonging, but this newsletter has already run pretty long, so I will write about them another time.

In conclusion

This is a moment a lot of us are trying to figure out how to build a broad base to take on some really evil folks in power, but how to do it in ways that don’t water down our principles and let very moderate and equivocating forces (or forces that believe in the system we had a year ago, which was already pretty awful for most of the people in my life). It’s definitely an art rather than a science, but attending this workshop got me thinking about some additional exploration I want to do in order to build connections to folks who are not yet “movement people” while also helping them connect the dots between their own struggles and those of other people. Within progressive organizing, that might be some of the most important work we can do right now, especially given how many ways our society has lost what little communitarian culture it had (that’s a whole other newsletter). I found some of this content really helpful and applicable not only to organizing among white people but frankly among the many overworked people in my life who don’t always have the time to think about things like this with all the competing needs in their lives. I was particularly excited to see how it connected to other work I’ve done, and I liked that it cut through some of the struggles many of us have had in racial justice work and education.

I hope you found it helpful as well!

And since sometimes I take notes that have NO context, the last line of my notes from this workshop just reads “Punch Up Collective.” Someone must have recommended them, referenced them, suggested that they do part of this methodology well. Since I don’t know why I wrote them down, I poked around, and I found their “Accessibility Checklist” a really useful tool for any of us trying to bring community together to solve the world’s problems. Our solutions are better the more people are able to participate, so check out this list (and other resources they recommend at the end of it).

Grateful to be up to this work with you.

Sandhya

I so appreciate this piece. It's a change I've personally hoped for, as 'allyship' as an end state never quite sat well with me. What I hear here emphasizes vision, common ground, healing, connectedness, and interdependence, alongside justice and solidarity -- and for me, that is where I want to be headed. <3